Description

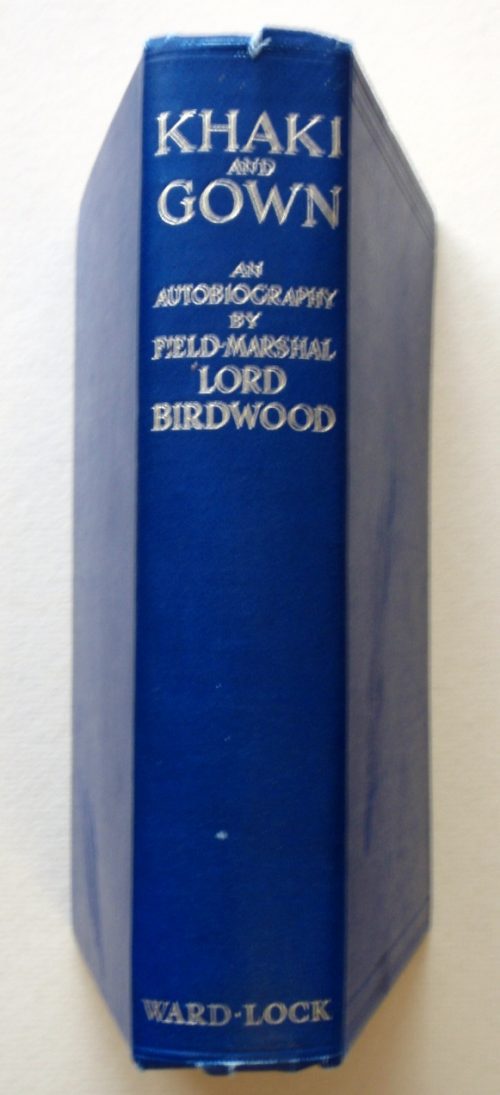

Title: Khaki and Gown – An Autobiography (Field Marshal Lord Birdwood)

Author: Lord Birdwood, Field Marshal

Condition: Very Good

Edition: 2nd Edition

Publication Date: 1942

ISBN: N/A

Cover: Hard Cover without Dust Jacket – 456 pages

Comments: An autobiography by an old soldier with tales of adventure from all over the world. The “gown” refers to his later years as Master of Peterhouse at Cambridge. Churchill served with Birdwood in the Boer War, and writes a glowing 2 page foreword.

William Riddell Birdwood was born at Kirkee, India, where his father was serving in the Indian Civil Service on 13 September 1865. Birdwood was educated at Clifton College, Bristol and at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. He joined the Royal Scots Fusiliers in 1883. From 1885 to 1899 he served in India as a cavalry officer with the 12th Lancers, 11th Bengal Lancers and the Viceroy’s Bodyguard. He served in South Africa from 1899 to 1902 on the staff of General Lord Kitchener. Promoted to Major General in 1911, he served as Secretary of the Indian Army Department from 1912.

In November 1914, Birdwood was tapped by Field Marshal Lord Kitchener, then British Secretary of State, to command a corps composed of the Australian and New Zealand troops in Egypt. He assembled the small staff allotted to a corps headquarters in those days from hand picked officers in India. The corps soon became known as the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps or ANZAC. Birdwood proved a good choice to command the Australians, accepting them for the way they were without trying to enforce all the customs of the British Army.

In March 1915, Birdwood was sent by Lord Kitchener to report on the naval attack on the Dardanelles. In a series of telegrams to Kitchener, Birdwood reported that the operation could not be carried out by the navy alone and that military operations would be required. He fully expected to command these operations, but was soon superseded by a more senior officer, General Sir Ian Hamilton.

Birdwood chose to attack with his corps at Gaba Tepe. It was a bold move but perhaps beyond the capability of his force. In deciding to land at dawn, he showed great confidence in their training. Later Birdwood developed an imaginative plan for outflanking the Turkish positions north of Anzac that was incorporated into the August offensive. It too was ultimately proven to be beyond the capacity of the troops.

Birdwood had great physical courage. Like many other senior officers at Gallipoli, he was contemptuous of danger, and at Gallipoli was very nearly seriously wounded as a consequence. Later in France in July 1917, he made a point of not moving his headquarters in order to escape shelling by a German 14 inch gun. He liked being with his men and was a frequent visitor to the front line. As a consequence, he was far more popular with his troops than the average First World War general.

Although a fine leader, Birdwood was not a great intellect. He was no great strategist or tactician. Birdwood was the only corps commander to oppose the evacuation of Gallipoli, although the operation was becoming extremely difficult tactically and was losing its value strategically. Nor did he have any great gift as an organiser. Nonetheless, he replaced Hamilton as GOC of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF) and was promoted to lieutenant general on 28 October 1915. On 19 November 1915 he took command of the Dardanelles Army.

After the Gallipoli campaign ended, Birdwood found himself again in command of a corps, I ANZAC, as of 17 February 1916, the original ANZAC having been split in two. He also became commander of the AIF, a post to which he was formally appointed in September 1916, and which he held until the end of the war.

In France, Birdwood found himself being bypassed by the GOC-in-C of the BEF, General Sir Douglas Haig, and the commander of the British Reserve (later Fifth) Army, General Sir Hubert Gough. His troops were committed to costly battles at Fromelles and Pozieres without his concurrence, and he was unable to prevent these senior commanders from interfering with operations at divisional level. Although he objected to some of the operations, he felt himself unable to dissent. Birdwood weakly agreed to commit his troops to a second, back-to-back tour of the Somme that resulted in 6,300 casualties for no worthwhile objectives.

Birdwood dismissed most of his senior commanders over the winter of 1916-17. As at Gallipoli, and indeed throughout the war, Birdwood’s preferred method for relieving subordinates was on medical grounds. Sometimes this left incompetent commanders in key positions awaiting illness. At other times, there was a natural embarrassment when, inevitably, the relieved officers were pronounced fit by medical authorities.

At Bullecourt, Birdwood once again acquiesced to Gough’s plans but after his corps was transferred to General Sir Herbert Plumer’s British Second Army in 1917, Birdwood at last began to emerge as a competent corps commander and become more assertive, insisting that his corps be rested after Poelcappelle. His conduct of operations at Third Ypres was characterised by both competence and caution.

On 23 October 1917, now the most senior officer in the Indian Army, Birdwood was promoted to full general, the only full general in command of a corps in the BEF. In November, his I ANZAC became the Australian Corps, with all five Australian divisions under his command, and the largest corps in France. He found himself under pressure from both Haig and the Australian government to replace British officers with Australians, which he did, even though many of those officers were old friends and colleagues.

The opening of the great German Offensive on 21 March 1918 found Birdwood in England, and he flew back to rejoin his corps. On 4 April 1918, it took over most of the Somme front. Over the next weeks, Birdwood was in command of one of the most critical parts of the whole British front.

On 31 May 1918, he was given command of the British Fifth Army, then regrouping behind the front. In the final offensive his Army played only a minor role, and it never included the Australian Corps.

In recognition of his wartime services, he was created Baron Birdwood of Anzac and Totnes in 1919 and toured Australia to great acclaim the next year. He commanded the Northern Army in India until 1925, when he was promoted to Field Marshal and became Commander in Chief, India. After he retired from the Army in 1930, he hoped to become Governor General of Australia, but despite the wishes of the King, the Scullin government insisted on appointing an Australian to the post instead.

He died on 17 May 1951.